5 Things To Know About Dorothea Tanning

The Tate Modern has just unveiled a major exhibition of Dorothea Tanning’s work, bringing together 100 of her pieces from across the globe – many of which are being shown in the UK for the first time.

With an extensive career and a collection of work delving into surrealism, abstract painting, textile sculpture and installation, you’d think Tanning (1910-2012) would be one of the leading names in modern art. However, along with many other female talents, she seems to have slipped through the cracks of our art history.

Visitors of the exhibition can look forward to finally celebrating the life and work of this pioneering artist, with a rare opportunity to experience her unique internal world. In the meantime, we’ve rounded up five things you need to know about Dorothea Tanning.

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik 1943

1. Her career spanned 70 years

This exhibition reveals how much Dorothea Tanning pushed the boundaries during her seven decade career through her abstract and sensual creations. Refusing to be pigeonholed, she continued to produce a variety of work right up until her death in 2012 – she was 101 years old.

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik 1943

Birthday 1942

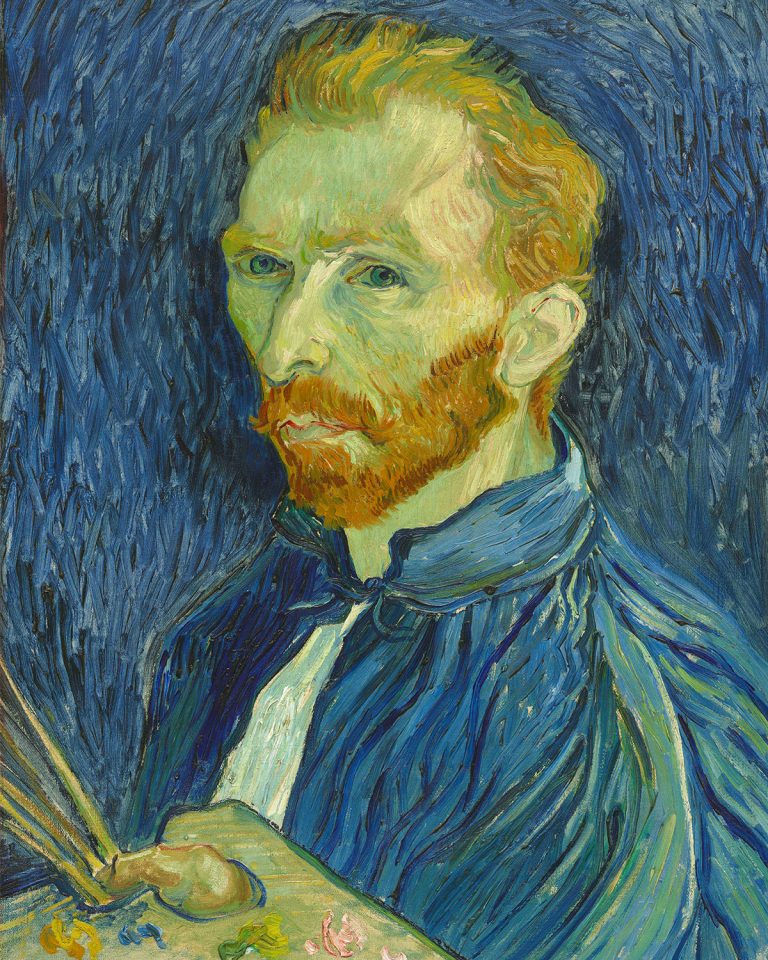

2. Her famous Birthday painting brought her and Max Ernst together

In 1942, German painter Max Ernst visited Tanning’s studio to consider her work for an exhibition of emerging female artists. He was captivated by her powerful self-portrait – and was in fact the one who named it Birthday. Ernst and Tanning married in 1946 and stayed together until his death in 1976.

Dogs of Cythera 1963

3. Although married to Max Ernst, she was an artist within her own right

Many know Tanning as a surrealist artist, or as the wife of the Max Ernst, but she didn’t want to be known simply as a ‘woman artist’ or ‘a surrealist.’ She was hugely influential and her work was constantly evolving – extending across painting, sculpture and writing.

Dogs of Cythera 1963

“There is no such thing (as a ‘woman artist’) - or person. It’s just as much a contradiction in terms as ‘man artist’ or ‘elephant artist." Dorothea Tanning

Dorothea Tanning in Great River 1944

4. She published two poetry books

Later in life when Tanning was 80, she began to focus on writing, producing a novel, an autobiography and poetry that featured in The New Yorker, The Yale Review and The Paris Review. One of her unpublished poems, Stain, explores her frustration of her marriage to Max Ernst defining her career – but not his.

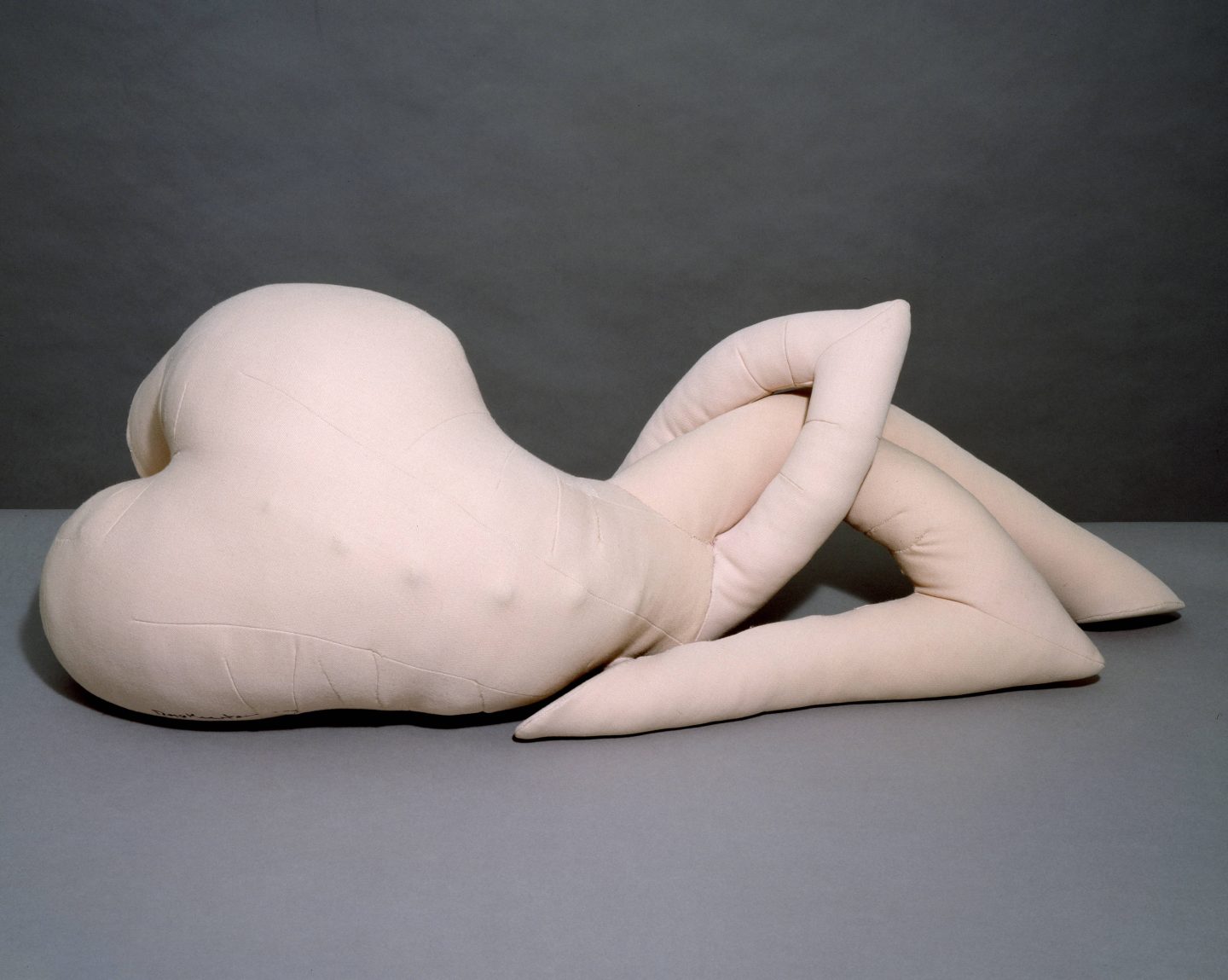

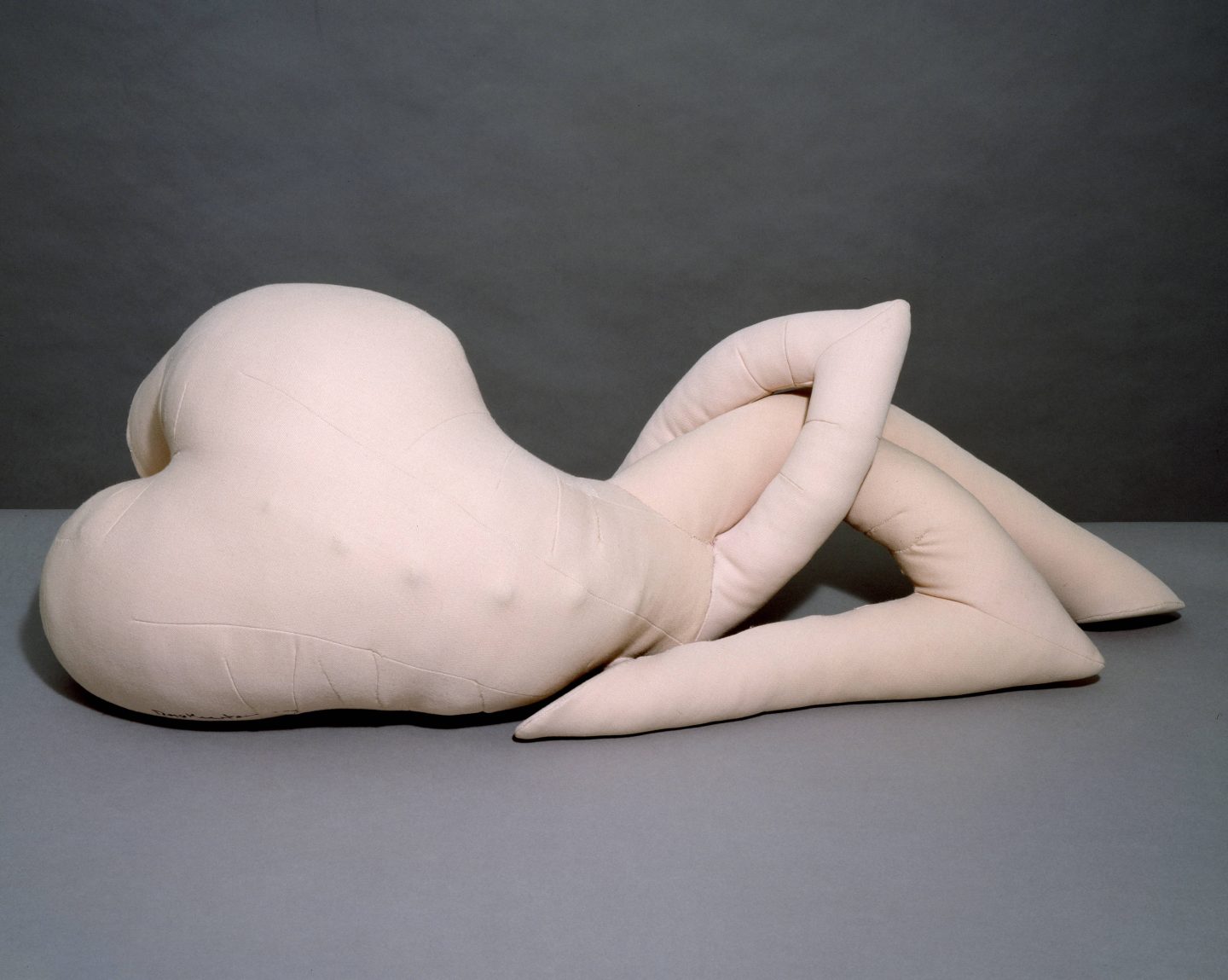

Nue couchée, 1969-70

5. She was a master at soft sculptures

In the mid 1960s Dorothea Tanning began a series of sculptural works she coined ‘living sculptures,’ made from soft fabrics, stuffed with wool and fashioned with jigsaw pieces and pins. They were often turned into erotic forms and inspired a legacy of their own in the world of surrealist sculpture. 5 of these figures are brought together in the room installation Chambre 202, Hotel du Pavot 1970-3 (Centre Pompidou), in which abstract bodies break through the walls and merge into furniture.

Nue couchée, 1969-70